Geology

Geology of Steele Creek Park: The Basics

By Jeremy Stout

(From Knobs and Knolls, Volume IX, Issue IV)

If you have ever wondered why the fields of the Steele Creek Park are so rounded, while the craggy knobs of the forests are so steep, then you are not alone. And it is not by chance, either. Most questions about the park’s landscape can be answered with just a few notes about the park’s underlying geology.

All of the rock units in the park (and in the region, for that matter!) are sedimentary. Sedimentary rocks are those that have formed from the accumulation and cementation of sediments like sand and mud, which form sandstone and shale respectively. Limestone is made up of very special kinds of sediments, the microscopic fossilized shells of planktonic creatures! Shale and limestone make up the vast majority of bedrock in Steele Creek Park.

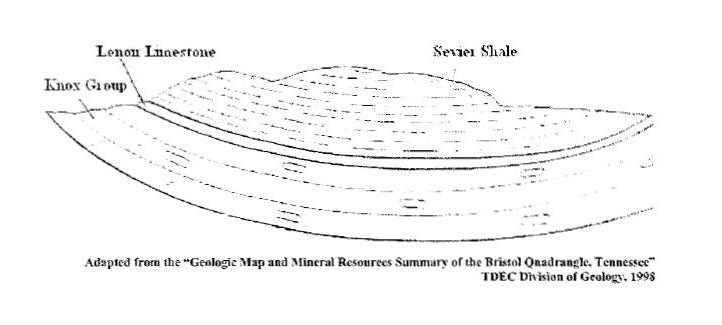

Basically, all 2,200+ acres of Steele Creek Park can be summed up in three major geological units, each stacked atop another. The bottom unit is the Knox Group, overlain by the much thinner Lenoir Limestone, with the Sevier Shale on top. (See the cross-sectional diagram below.)

The “Knox Group” actually refers to several different rock types of Upper Cambrian to lower Ordovician age that occur in the region. This unit is found throughout much of the northeastern portion of Steele Creek Park. Though this group contains other rock types, limestone and dolomite (a rock very similar to and formed from limestone) characterize the Knox at the park. There are not many outcrops to readily observe, but the sinkholes that dot the multi-use fields are testament to the carbonate bedrock underneath!

While walking along the beach below the Nature Center and lodge, it is impossible not to notice the large, blue-gray boulders jutting up from the ground. This is one of the few places in the park, as well as in the area, where you can see the Lenoir Limestone! These boulders are beautifully rounded due to a form of chemical erosion. Believe it or not, ordinary rainwater will actually dissolve limestone over time, leaving smooth and rounded outcrops. It is also important to note that it is the Lenoir (through processes of the same chemical erosion) that is home to the park’s Quarry Cave.

Finally, when hiking the park’s trails through the ridges and ravines, you will undoubtedly notice the shale of the Sevier Formation. This is the brown, crumbling rock that can peel apart to nearly paper-thin sheets. Not nearly as susceptible to chemical erosion, shale is very brittle and quite weak to physical weathering. This is why the fragments you find are nearly always very angular in shape. This is the thickest and topmost rock unit in the park, but also makes up the majority of the park’s bedrock land area. Some units of the Sevier have a dark gray coloration (called black shale), and for this reason is often misidentified as slate.

Presented here are just a few notes about the bedrock geology of Steele Creek Park. There are certainly volumes more to be written, but I do hope that you will come out soon to see some of these formations mentioned firsthand, as winter is truly an excellent season for geologizing. Happy exploring!